During my first year of graduate studies in architecture at the University of Colorado, I wrote a few articles for our department’s student newspaper. One of my articles, an interview with renowned architect William Caudill, was published in the 1983 issue of CRIT magazine. I resurrected the article in response to discussions in our office about aesthetics in architecture, the role of the computer in our work, and the future of our profession.

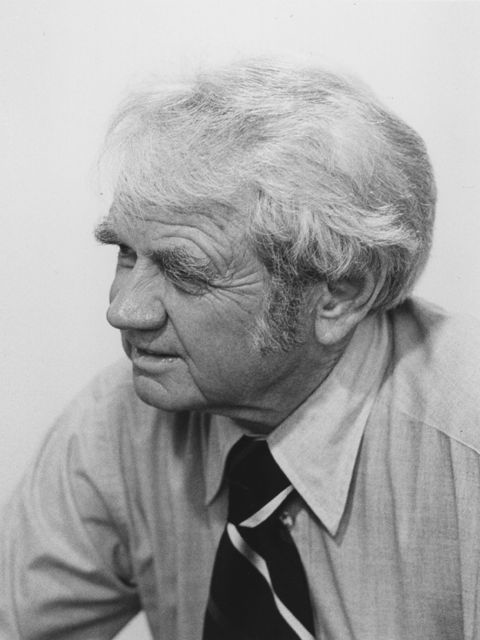

Bill Caudill was gracious with our time together when we met in Vail in the winter of 1982. One of his first projects was for the design of a new high school in Blackwell, Oklahoma, mere miles from where I farmed during the summers with my Uncle Lawrence between 1966 and 1976. The Blackwell High School project received a number of design awards and launched his firm, Caudill Rowlett Scott, as one of the leading architecture firms for educational facilities in the US. Bill died unexpectedly in 1983, shortly after my interview with him. The following is an exact transcript of the 1983 article in its entirety.

——

Bill Caudill is the Chairman of the Board of Caudill Rowlett Scott Architects Planners Engineers of Houston. Mr. Caudill has authored eleven books on architecture, has lectured extensively throughout the US, and is a member of the Board of Directors of the AIA. He was interviewed by Nathan Good, who is currently in his first year of the Graduate Program in Architecture at the University of Colorado.

GOOD: As you might know, Michael Graves will be speaking in Denver next week on the topic of “Figurative Architecture.” Do you share my concern about a sector of the profession’s opiated attraction to the Post Modern Classical movement, especially in lieu of the need for an energy-conscious architecture?

CAUDILL: Well, you’re crying in the dark because Michael Graves is hero number one all over the country, and also in our firm with the young people. See, he was a hero before he even built anything much. It’s his drawings that have made him a hero.

GOOD: To what do you attribute Michael Graves’ present popularity?

CAUDILL: When I was in school during the Great Depression, they came out with these great big movies about the rich, their chauffeurs, plantations and great movie stars. Well, Michael Graves is coming in and people just love his things, the fantasy buildings, and then he comes up with wonderful portraits of these buildings. The heroes are not just Michael Graves but Bob Stern, Philip Johnson, Peter Eisenman, and a number of others.

GOOD: As a cornerstone member of the status quo, do you view Graves and the other camp Post Modernists as a personal or professional threat?

CAUDILL: I haven’t ever said anything bad about Michael Graves because he is a fine, fine, person, and you don’t just fight heroes. We spent a hell of a lot of research time on this Post Modernism, not because it is a threat, but because it’s an adjustment. We can’t fight it and you guys shouldn’t be fighting it. Go along. Look at its roots and its meaning.

GOOD: Has your research revealed to you how these “heroes” have made their climb to the top of the popularity ladder?

CAUDILL: The thing is, these innovative designers are deep thinkers. They write, though abstractly, very intelligently. Their heroes were not architects but were linguists. I gave my daughter some things to read that Eisenman and Stern had written and she said to me, “Daddy, you get your inspiration from your clients and their site, where they live, the climate they have, and their idiosyncrasies. These people don’t have clients all over the world like you do. They’re in academia and so they go to their literary sources for inspiration.” Our research revealed that our present-day heroes, their heroes, and their heroes’ heroes said the same thing that they are saying now. Once we understand who they are, what they are, and what they’re saying, we’re not afraid of them. We can understand and appreciate what they’re trying to achieve. In fact, we admire them all the more. They’re not satisfied with banality.

GOOD: Their work seems to be a reaction against or a response to the architecture of the last several decades. Whether they’re a fad or not, they are bound to have some impact on the next generation of architects and designers. What form do you think that their influence will take?

CAUDILL: I think the reason the Michael Graves are going to lose out is that they are not looking at the total problem. They are only looking at the aesthetic problem. Philip Johnson is credited with saying, “There is only one problem in architecture, that of aesthetics.” And Mies was close to that kind of thing with his complete disregard for regionalism and functional exactitude. Some architects choose aspects they can handle best like problems in form, function, economy, structure, construction, or energy. Some of the worst buildings I have seen in all my life are very energy conscious. There are damn few really good looking energy-conscious buildings. The architects who did them lacked the total approach. Energy is a very serious consideration. It can give us a new kind of aesthetics. We know that Michael Graves and Chuck Moore have systems of aesthetics but we need a system of aesthetic for energy.

GOOD: A couple of years ago you were quoted as saying, “Processes don’t create good design, good designers create good design.” How do you envision a system of aesthetics evolving to create a good design?

CAUDILL: All of the schools are trying their best to find some sort of a design methodology that will take the place of good designers. Can’t be done. I have a theory that it is the medium that the designer uses that affects what the building will look like. When I was teaching at Rice several years ago, chipboard came along. People stopped drawing and started working with chipboard, and their buildings started to look like chipboard buildings. And I know some architects that actually took a sample of chipboard to their concrete consultant and said, “We want the same color and texture as this chipboard.” That’s the absolute truth. There’s a building on Harvard’s campus that Yamasaki did that looks like a blown-up chipboard model!

GOOD: That reminds me of a book that came out in 1967 or 1968, The Medium is the Message by Marshall McLuhan.

CAUDILL: Marshall McLuhan was one of the heroes of architects in the 60s. One of my partners used to say, “The process is the product,” and that was when process meant everything. We got in these in-house arguments over this issue; my point being that I don’t give a damn whether the process is the product or not. If the product stinks then so too must the process. Today, drawings have more of an influence on architects than actual buildings. Buildings are beginning to look like Michael Graves’ sketches. It is a time of paper architecture. Always been. Architects are more influenced by drawings of buildings than by real buildings.

GOOD: What do you anticipate that architects’ next medium will be?

CAUDILL: It’s going to be real interesting to see what happens to our buildings when we start playing around with the computer a little more. We’ve only gotten involved with them a bit, but I want to get involved with them to the point where I lose my desire to touch a pencil. What a potential! My clue came after we had a computer consultant come into our firm to develop renderings from some of our sketches. After reviewing the computer’s drawings, one of the designers in our firm remarked how the computer consultant had taken too many artistic liberties. That really was interesting. If we could get someone on the the computer, what kind of designs could he or she produce? It’s going to happen and I don’t want to miss out on it.

“It’s going to be real interesting to see what happens to our buildings when we start playing around with the computer a little more. We’ve only just gotten involved with them a bit, but I want to get involved with them to the point I lose my desire to touch my pencil. What a potential!”

— William Caudill, 1983